60 years of stagnation: A call to campaign for mindset change

At 60, Malawi is still mired in corruption, poverty and tribalism; and is largely food insecure. How then can Malawi successfully fight its problems and be counted among stellar performers in Africa?

By Joseph Kayira

Torn between the lure of deepening democracy, maintaining peace and political stability – and the failure to root out corruption, build the economy and bail out majority of the people out of the vicious cycle of poverty – Malawians remain poorer than the average global citizen, six decades after attaining independence.

The World Bank says, “Malawi remains one of the poorest countries in the world despite making significant economic and structural reforms to sustain economic growth. The economy is heavily dependent on agriculture, which employs over 80% of the population, and it is vulnerable to external shocks, particularly climatic shocks.”

Sixty years of independence and 30 years of democracy should be long enough for Malawi to have mastered the terrain of democracy and how to use its attendant freedoms as well as the responsibilities that come with it to graduate to a much-desired low middle-income nation. But at 60 Malawi is mired in corruption, poverty, tribalism and is largely food insecure.

How then can the present generation avoid passing the burden of poverty, high and unsustainable public debt hovering at over K15 trillion and deep-seated poverty to future generations? How can Malawi successfully fight its problems and be counted among star performers on the continent? How can Malawi tackle the root causes of its problems which date back to the 1960s?

Opinions vary on Malawi’s misfortunes; but both multilateral and bilateral donors agree this country of over 20 million people needs to do more to turn things around. Authorities have been urged to stay on course on economic reforms. Malawi must strive to create a sustainable and stable economy says the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The Kamuzu Banda era

The early years of Malawi’s independence under founding president, Dr Hastings Kamuzu Banda were synonymous with sustainable development and self-reliance. There is a general agreement that despite Banda’s reign being undemocratic, development achievements in the country could be witnessed and people’s basic needs were met by the government until 1994, when these gains were eroded over time. ”When Banda emphasized his three developmental goals of food, clothing and shelter, they were well received by many Malawians because these aspects were central to the umunthu/ubuntu philosophy.”

Real stagnation started to manifest when Banda became so autocratic in the early 1980s. His ruthless repression of political dissent at home instilled fear in his people. While the first years looked promising, his policies became unpopular with the West, key financiers of the national budget and the economy. But Banda defended his foreign and domestic policies as ‘necessary evils’.

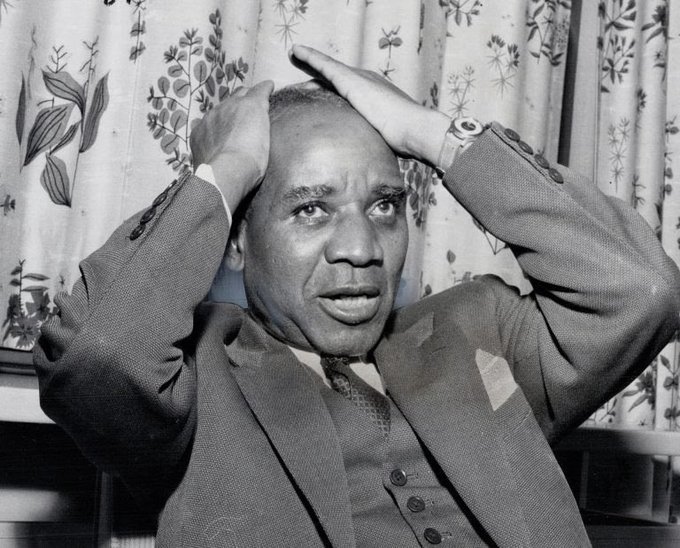

Malawi’s founding president, Ngwazi Dr Hastings Kamuzu Banda

Western states ignored widespread allegations of human rights abuses until the early 1990s allegations of human rights abuses until the early 1990s when economic decline, the beginning of the end of apartheid, and the thawing of the Cold War led to a resurgence of protest, both foreign and domestic. In the face of this pressure, Banda allowed for a 1993 referendum on multiparty democracy, which led to multiparty elections the following year. He stood and lost as the MCP presidential candidate, and Bakili_Muluzi, leader of the United Democratic Front (UDF), formed a government.

Successes and failures in a new dispensation

Scholars, experts and politicians say 60 years of independence come in form of a mixed bag for Malawi – more after attaining multiparty democracy in 1994. They come in form of achievements, gains and challenges; posing the question – what does the future hold for Malawi?

Once a bread basket in southern Africa, today Malawi is struggling to feed its people. Already, 5.7 million people are estimated to be acutely food insecure in between now and March 2025. World Food Programme (WFP), says the 2023/2024 season has been greatly affected by the El Niño weather conditions. Overall, the country experienced a late and erratic onset of effective planting rains, inadequate rains, reduced rainy days as well as prolonged dry spells which have significantly affected crop production prospects.

A mix of external shocks and poor implementation of agricultural policies such as the Affordable Input Programme (AIP), a government subsidy programme that targets poor farming households, has pushed millions in need of food. In a country where the agriculture sector employs over 80 percent of the population, food security remains a critical issue. The AIP has not demonstrated any economic empowerment of the beneficiaries but rather it has created dependency. It has also created an elicit syndicate of procurement of the AIP supplies

Recurring droughts afflict Malawi’s agriculture sector, threatening the livelihoods of Malawi’s smallholder farmers, who constitute 80 percent of Malawi’s population. Thirty-eight percent of Malawians live below the poverty line, and 47 percent of children are stunted.

It is not only in agriculture where problems persist. There are also sad stories in the education sector, where in many parts of the country children are still learning under trees because the public purse cannot finance the construction of school infrastructure in all the 29 districts and towns across the country.

The health sector is equally bleeding as government struggles to meet the ‘Abuja Declaration’ and other instruments such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals to address health challenges. When African Union member states met in Abuja back in April in 2001, delegates committed to allocating 15 percent of their national budgets to finance health. For countries like Malawi, mobilizing resources to address critical issues in health remains mammoth task.

According to the Malawi Medical Journal, globally, critical illness causes up to 45 million deaths every year. The burden is highest in low-income countries such as Malawi. Critically ill patients require good quality, essential care in emergency departments and in hospital wards to avoid negative outcomes such as death. Little is known about the quality of care or the availability of necessary resources for emergency and critical care in Malawi.

According to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), the top ten causes of death in Malawi are: HIV/AIDS (18.17%); Respiratory infections and tuberculosis (12.96%) Cardiovascular diseases (11.6%); Maternal and neonatal disorders (9.36%); Neoplasms (7.8%); Enteric infections (6.27%); Neglected tropical diseases and malaria (5.76%); Digestive diseases (4.34%); Other infectious diseases (4.29%); Other non-communicable disease (3.99%).

At the end of the day, this remains a huge cost to the heath budget, and may take years before Malawi meets its health obligations.

All not lost: nurturing prospects of a brighter future

But former president Muluzi is upbeat about the future. He also looks back at 60 years of independence with pride having achieved democracy in 1994, especially after 30 years of dictatorship.

“I feel proud that we have reached this far. I must hasten to say that there is still a lot to be done to take Malawi to another level. Poverty is still an issue; the poverty levels are still high. I think we must ensure that resources in our national budget should reach the ultra-poor citizens.

“People need development in rural areas in terms of schools, good roads and that they should have access to potable water. So, in these 60 years of independence we should have done better. There is room for improvement,” he says.

Politician and legislator Henry Chimunthu Banda, who is also former Speaker of Parliament says while there are good reasons to be proud of independence and self-rule, apparently failures and successes overshadow each other.

He told one of Malawi’s dailies, The Nation that “The question would be: have we reaped anything from the independence we achieved in 1964? Has it given us the fruits that our forefathers fought for? This is highly debatable.”

He cites tribalism and corruption as some of the failures that stagnate development and progress.

“There was a time when tribalism was almost forgotten but it is sad that over time matters of tribalism, although they are swept under the carpet, are a reality. When you look at how certain appointments are done, and the voting pattern, they show elements of people embracing a candidate based on tribal affiliation.

“It is something we shouldn’t be promoting under democracy. Corruption too has gone on almost through the entire period and is denying citizens full enjoyment of democracy,” Chimunthu Banda told the daily.

The Episcopal Conference of Malawi (ECM), says corruption is a difficult vice to fight as it has taken deep root all over Malawi.

In one of its pastoral statements ‘Call for a relentless fight against corruption’ the ECM says: “It [corruption] causes untold suffering to the vast majority of ordinary Malawians who face crushing poverty on a daily basis. Unfortunately, even those tasked with fighting and eliminating corruption are too often sucked into it.”

Equally crucial, is the Malawi Vision 2063 Malawi Vision 2063, an overarching policy paper which identifies ‘Mindset Change’ as one of the enablers towards an ‘Inclusively Wealthy and Self-reliant Nation’. Since adopting the Vision, mindset change has become a catchphrase that needs deeper reflection to clarify thoughts and pursue coherent action for good governance. It says Malawians have a critical role in making sure that the country achieves its aspirations.

Tobacco is Malawi’s top foreign exchange earner

University of Malawi lecturers, Eston Frank Mkumbwa and Mzee Dr Hermann Yokonia Mvula say patriotism can help to transform Malawi. They say political leaders are blamed due to their behaviour of looting public money and saving their personal interests at the expense of Malawians.

Mkumbwa and Mvula argue: “In Malawi, experiences have shown that indeed political leaders are to be blamed for Malawi’s almost stagnation status since they are policy makers and implementers. Most political leaders Malawi has witnessed are good at making polices but bad at implementation. Should we talk of how Vision 2020 died a natural death? We are now talking of vision 2063. Are we really going to achieve it?”

They add that Malawi has failed to progress due to a number of factors which include; mediocre and non-visionary leadership, unpatriotic citizenry, corruption, and perhaps something to consider critically, the misuse or abuse and misunderstanding of principles of democracy.

“Corruption by both the governors and the governed remains the biggest factor, which stems forth from people who don’t love their country,” they say.